In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

If and when mankind spreads to the stars, many of the problems we experience on Earth will follow us to new worlds. Medical issues could become more complex as we encounter whole new ecologies. And sharing medical knowledge could be complicated by the vastness of space. In the mid-20th century, Murray Leinster, one of the most entertaining and creative of science fiction’s early masters, imagined a cadre of uniformed public health officers who travel the stars like the knights errant of ancient legend, helping the needy and righting wrongs. At this moment in time, as we face a worldwide pandemic, these tales and the lessons they contain have suddenly become very timely.

Up until recently, I’d wager that most people did not have any idea what uniformed public health officers did for a living. But during the current pandemic, we have frequently seen them at the podium, discussing medical measures to combat the virus, such as social distancing and vaccines. In addition to these bureaucratic roles, members of the public health service serve in many different capacities. They work at seaports and airports to screen people and cargoes coming and going, they oversee food processing and drug manufacture, work at far-flung government hospitals, and travel to the front lines to investigate disease outbreaks around the globe. Their efforts are indispensable in keeping people safe and healthy, and can often put them in dangerous situations.

About the Author

Murray Leinster (the pen name of William Fitzgerald Jenkins, 1896-1975) was one of the premiere writers in the early days of science fiction, beginning right after World War I and continuing into the 1960s, when I was first reading my dad’s Analog magazines. His story “First Contact” gave a name to the entire sub-genre of stories portraying meetings between alien races. His story “Sidewise in Time” gave its name to the Sidewise Award for Alternate History. And his Med Ship series was one of the first fictional explorations of the challenges doctors might face in space. Remarkably, while Leinster was known for the science in his stories, he dropped out of high school and never had the chance to attend college, and was self-taught in a wide range of fields. I previously looked at his work in my review of the NESFA Press book entitled, First Contacts: The Essential Murray Leinster, and if you are interested in learning more about the writer and his work, you can find that review here.

Like many authors whose careers started in the early 20th Century, you can find a number of his stories and novels on Project Gutenberg, including a few Med Ship stories.

Doctors in Space!

Medical issues have always figured into science fiction from the earliest days of the genre, being central to the seminal tale Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Often, the medical situations were a source of horror and suspense. As the field matured, however, writers began to look at the impact science fictional settings might have on the medical profession. The first examples I personally encountered are the subject of today’s review, Murray Leinster’s Med Ship series, which imagined uniformed public health officers as a kind of medical knights errant or paladins, wandering the stars to save the sick. Another long-running medical series was James White’s Sector General stories, set in a multi-species hospital in space. One of my favorite authors, Alan E. Nourse, a practicing physician, wrote only one book on space medicine, Star Surgeon, and it’s a shame he didn’t write more (one of his short medical stories, “The Coffin Cure,” is among my favorite tales of unintended consequences).

On television, doctors and medically-themed episodes have been central to the many incarnations of Star Trek, starting with the curmudgeonly and entertaining Doctor Leonard McCoy in the original series (with pithy quotes like, “He’s dead, Jim,” and “I’m a doctor, not an escalator”). And of course there are many more examples of doctors and medical issues in science fiction, which you can explore in this article, another of the online Science Fiction Encyclopedia’s excellent summaries of the themes of science fiction.

Med Ship

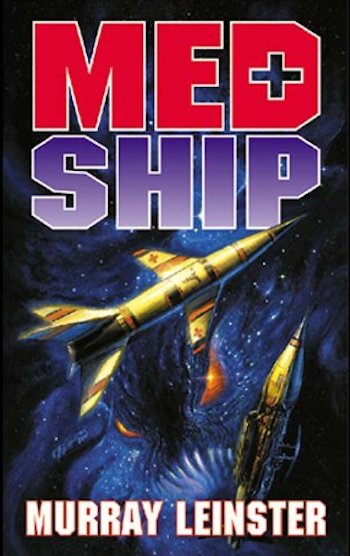

This book is a nice collection of all eight of Leinster’s “Med Service” tales, released by Baen Books in 2002. The book has one of those shiny metallic covers Baen favors, with graphics a little more restrained than most of their books (and all the better for it). Cover artist Bob Eggleton, one of the last remaining masters of the art of painting pointy spaceships with big fins, deserves credit for a beautiful cover. He also hints at a menacing monster in the background, a physical representation of the medical threats faced throughout the book.

The book introduces us to Doctor Calhoun, a uniformed Med Service officer, and his alien companion, a “tormal” called Murgatroyd. Together, they travel between the stars on Med Ship Aesclipus Twenty (Aesclipus, more often spelled “Asclepius,” is the Greek god of medicine), a tough and capable vessel that displaces fifty tons. The ship travels between stars via faster-than-light “overdrive.” And while Aesclipus Twenty can land with rocket propulsion, Leinster has developed an interesting type of launch systems for these tales. Gigantic landing grids, often a mile in diameter and a half-mile long, draw power from planetary ionospheres, and in addition to powering the local civilization, can bring ships in and lift them with force fields. The properties of these landing grids often shape the plots of the tales. Humanity is the sole intelligent species in this universe, and there are plenty of new planets to colonize. The stories are episodic, like many literary and television series of the era, with no overarching story arc and each tale independent.

Buy the Book

To Sleep in a Sea of Stars

Your enjoyment of these tales will depend quite a bit on whether you are willing to accept the idea of a doctor traveling with a laboratory test animal. Murgatroyd the tormal is a unique creature, modified so that he cannot feel injections or blood draws, and whose metabolism is uncannily (and improbably) almost the same as a human’s, but with a remarkably effective immune system. In addition to being able to detect poisons, dangerous odors, or other health threats, Murgatroyd can be infected with diseases that affect humans in order to produce antibodies in a very short period. While Leinster takes pains to explain that this does not hurt or threaten Murgatroyd, those who oppose animal testing may find this aspect of the stories troubling.

Murgatroyd is not described or explained in exact detail, but he is furry, simian, and while he generally walks on all fours, he likes to rise on his hind legs, imitate the humans around him, and drink coffee. He is an affectionate creature, and both likes and is liked by the humans he interacts with. He also acts as a sounding board for Calhoun, who despite not receiving answers, likes to chat with him during their missions (a clever way to weave expository “As you know, Bob,” conversation into the tales). The name Murgatroyd has humorous connotations, as the euphemism “heavens to Murgatroyd” was in use as an alternative to swearing when the stories were written. And Calhoun and Murgatroyd exhibit the same close and loving relationship you find today between police officers or military personnel and their working dogs. Leinster used animal sidekicks in other stories to good effect, with his Hugo-winning story “Exploration Team” featuring a human explorer on a hostile planet, aided only by genetically engineered bears and a trained eagle.

The first story in the collection, “Med Ship Man,” which appeared in Galaxy in October 1963, finds Calhoun and Murgatroyd arriving to conduct a planetary health inspection on a world new to them, only to find everyone gone. Calhoun’s first thought is plague, but instead he sees signs of a hasty evacuation of the city surrounding the landing grid. A man on an arriving liner insists on being dropped in an escape pod, and Calhoun learns that he is a real estate speculator with a briefcase full of bearer bonds. Calhoun’s suspicions are aroused, and he eventually discovers the connection between the mystery and the stranger. We learn Calhoun holds no pity for anyone who puts others at risk.

The next story, “Plague on Kryder II,” is from Analog, the December 1964 issue. Calhoun finds a plague on the eponymous planet, and this particular disease can kill even the normally immune tormals, which puts his beloved Murgatroyd at risk. It turns out the plague in this story has been created by criminals to extort colony worlds, and Calhoun has his hands full figuring out the details and thwarting their scheme. Those who murder for profit, and besmirch the reputation of the Med Service, find no mercy from Calhoun.

The Mutant Weapon (originally published under the title “Med Service”) was published in Astounding in August 1957. Calhoun and Murgatroyd arrive at a planet being prepared as a new colony. The operators of the landing grid are surprised to see them and use the grid to try to shake their ship apart. Calhoun lands using his rockets, and finds the body of a man who has apparently starved in the middle of a field full of edible plants. Then a “girl” tries to kill him (however, it turns out that she is not, as I first assumed, a youngster, but rather a fully grown woman—like many authors of his time, Leinster has some antiquated ideas about gender). It turns out the advance party for the new colony has been deliberately infected by invaders who want to take the planet for their own. Calhoun must first cure the advance party of their disease, and then defeat the invaders before they can unload their own colony ships. At this point, I began wondering if Calhoun’s whole job involved countering deliberate malicious acts, as if dealing with naturally occurring hazards was deemed not interesting enough to hold the reader’s attention.

“Ribbon in the Sky” was published in Astounding in June 1957, making it the first of the Med Ship stories to appear in print. Calhoun arrives in unknown territory due to someone having programmed his navigation system improperly. He finds a planet surrounded by a ring of sodium dust to alter its climate, and discovers a lost colony, split into three warring cities, all believing that the others will infect them with a deadly plague. There is a Romeo and Juliet relationship between young lovers from two cities, which suggests the situation is not what people think it is, and Calhoun must deal with prejudice and ignorance as much as disease in order to heal this long-isolated branch of humanity.

“Tallien Three” (originally published as “The Hate Disease”) appeared in Analog in August 1963. Calhoun’s arrival is interrupted by an attempt to shoot down Aesclipus Twenty with a missile. The colony is dealing with what appears to be a disease causing insanity and hatred in its victims. But it is an odd sort of insanity, one which allows its victims to cooperate with each other and accomplish complex tasks, as demonstrated by that hostile missile launch. The factor causing the disease to spread turns out to be quite clever, the local officials are unreliable, and Calhoun again rises to the occasion.

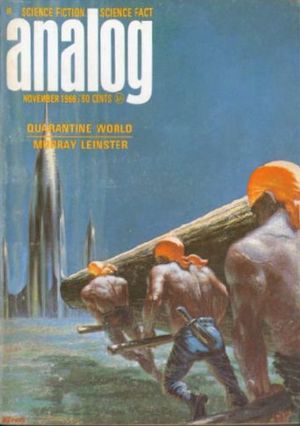

The story “Quarantine World” (from Analog, November 1966) is one I remember well, along with the Kelly Freas cover adorning the issue:

(Seeing this picture on a Facebook group recently is what initially reminded me of the Med Ship series, and I suspect it was posted because the story has become so topical in recent months.) Calhoun has arrived at the planet Lanke, finds the medical situation a bit too perfect, and smells a rat. When a disease-stricken terrorist attacks a meeting, the hidden problems are revealed. It seems that Lanke is at odds with a planet that has been quarantined because they perceive it to be full of disease. The leaders of Lanke had kept this situation from Calhoun because they feared the economic damage a quarantine of both worlds might bring. Interestingly enough, no one suffers from the illness on its planet of origin. Calhoun must solve this mystery and head off the pandemic the terrorist brought to Lanke.

“The Grandfathers’ War,” from Astounding in October 1957, is a tale of a generation gap, a concept much in vogue during those days, with this gap exploding into open warfare. Faced with the impending explosion of an unstable sun, the colony of Phaedra is working to establish a new colony on Canis III; they have sent their children not only to build it, but with the goal of keeping them safe. The young people, though, have been worked to the breaking point and doubt their parent’s motivation. They refuse to continue to toil away on behalf of their elders or even accept the arrival of their parents to take away the hard-won fruits of their labor. The story is very much a product of its time, and some of the assumptions about generational differences, and especially gender roles, will amuse (if not infuriate) modern readers.

The final story, “Pariah Planet,” from Amazing, July 1961, is a tale of prejudice as much as disease. Calhoun finds himself in an area where the Med Service has fallen into disarray, visiting a planet, Weald, that has not been seen for quite some time. The people are very defensive, terrified of a plague that has marked its victims on the nearby world Dara as “blueskins.” For years, Weald’s leaders have used the blueskin threat to scare their inhabitants into following government direction, uniting against a common “enemy.” Weald is frightened enough to consider genocide in order to defend themselves. Dara, on the other hand, is wracked by famine, with its people desperate enough to resort to violence. Again, Calhoun must not only deal with disease, but also defuse the situation and avoid a full-blown war. He also bonds with a young woman from the quarantined world—the only time in the series he comes close to romantic attachment. The story ends with Aesclipus Twenty approaching the next planet on their schedule and Calhoun telling Murgatroyd, “Here we go again.”

Final Thoughts

I certainly enjoyed my timely revisit to the Med Ship series. It has its dated elements, but Calhoun and Murgatroyd are engaging protagonists and the medical puzzles Leinster constructed are clever and engaging. The stories are well worth seeking out, either on Project Gutenberg, or in old magazines or collections.

Now it’s my turn to shut up, and your opportunity to speak: Have you encountered any of the Med Ship stories, and if so, what are your thoughts? Are there other Murray Leinster stories you’ve particularly enjoyed? And what other medical science fiction stories have you read and would recommend? I do ask that you try to keep current politics out of the discussion—as in the stories, pandemics too often bring with them fear, anger, and distrust when empathy and understanding is most needed.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.